Plants of Gunnison, Colorado

This guide to the plants of Gunnison, Colorado features some of the most common and iconic plants in the ecosystem around Gunnison, including many of the wildflowers for which this region is famous. If you love learning about the flora of this area, also check out the guides to wildlife and insects.

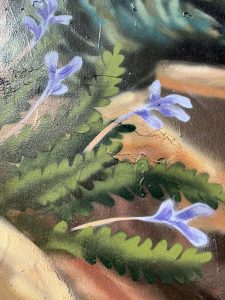

Mural at IOOF park

This guide was designed to accompany the mural at IOOF Park, located at 124 E. Virginia Ave. in downtown Gunnison. Each species of plant featured on the mural is listed here, along with a photo of its likeness on the mural. Can you find all the plants of Gunnison?

About the author

Patrick Magee, Ph.D., is the Associate Professor of Wildlife & Conservation Biology at Western Colorado University in Gunnison. In addition to teaching courses at Western, Dr. Magee is a wildlife biologist specializing in wildlife conservation efforts across the American West.

Click or tap on the photo to learn more about that species.

Alpine Pennycress

Latin name: Noccaea fendleri

Other names: Rock Pennycress, Mountain Candytuft, Wild Candytuft, Fendler’s Pennycress, Glaucus Pennycress

Plant Family: Brassicaceae, Mustard Family

Native to the western United States, this wild white mustard grows in rocky habitats from lower elevation montane zones to the alpine tundra. This early bloomer has a cluster of flowers (raceme) on the top of the plant, giving an attractive appearance and the common name candytuft. Each of the small flowers has four showy petals that attract many insect pollinators, including numerous butterflies who lay their eggs on the plant. The resulting caterpillars feed on the host. At the base of the plant leaves form a rosette or circular structure and then alternate up the stem. This perennial plant produces pods, each containing two seeds.

(Sources: Colorado Wildflowers – coloradowildflower.com; science.halleyhostign.com, RMBL.org)

Fireweed

Latin name: Epilobium angustifolium

Plant Family: Onagraceae, Primrose Family

“The plant that turns scars into flaming beauty!” —M. Durant, 1976

With its blazing fuschia or magenta flowers, fireweed features prominently in the late summer wildflower drama in the Rocky Mountains. Fireweed aggressively colonizes disturbed sites, after wildfires, avalanches, landslides, logging and mining operations, and even after bombing raids – in Great Britain is was called Bomb Weed during World War II as it pioneered the vegetation recovery in war torn areas in London and across the countryside. That is the essence of fireweed, a disturbance associated generalist wildflower found all over the Northern Hemisphere, especially at higher latitudes (circumboreal plant). This perennial species has a substantial root and rhizome system under the soil with roots more than 17 inches deep and rhizomes up to 20 feet long. Rhizomes allow the plant to send up shoots and quickly spread and colonize disturbed sites, especially after fires. The first plant that returned after the 1980 eruption of Mount Saint Helens was fireweed, and it blanketed the ashy ground with its colorful blooms. In addition to the colorful flowers, the lush green shoots of summer transform to a flammulated red, heralding the coming of winter. While the plant excels at reproducing asexually through sprouting from underground tissues, it also produces prolific seeds – up to 500 from a single flower and 80,000 from one plant! The seeds boast feather-like plumes that carry them aloft on the wind. Some seeds travel over 180 miles to a germination site. When the seeds land on the soil, they readily germinate in post-disturbance, mineral soils where plentiful light strikes the ground. Fireweed feeds a variety of wildlife including elk, deer, moose, bears, muskrats and caterpillars. It is also highly attractive to pollinators, acting as the main host plant for five butterfly species. Humans have traditionally used fireweed for both food and medicinal purposes – the entire plant is edible!

(Sources: khkeeler.blogspot – A wandering Botanist; Colorado.edu – Natural History Museum; fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants)

Fireweed. Photo by Pat Magee.

Penstemon

Latin names: Penstemon unilateralis and Penstemon strictus

Other names: Penstemon or Beard Tongue; One-sided Penstemon (P. unilateralis) and Rocky Mountain Penstemon (P. strictus)

Plant Family: Scrophulariaceae, Figwort Family

Native and unique to North America, penstemons colorfully decorate landscapes across the continent, including in the southern Rocky Mountains and the Four Corners region. About 60 species are native to Colorado. One-sided penstemon and Rocky Mountain penstemon favor relatively lower elevation life zones in sagebrush, pinon-juniper and ponderosa pine ecosystems. These purple, semi-evergreen, perennial wildflowers have a long flowering period and support large populations of pollinating insects. The tubular flowers welcome bees and other pollinators with their bright colors. They are also drawn into the flower with nectar guides (like flashing lights directing bees to the center of the flower) and a long, hairy stamen called a beard tongue. This forces the bee deeper into the flower, where it comes into intimate contact with the flower’s pollen. These insects effectively gather and then carry the pollen to neighboring penstemon plants, thus cross-pollinating them. Purple-ish penstemons, representing about 80 percent of all the 270-plus species of penstemons, tend to attract bees specifically and have other traits that match the structure of their bee pollinators. In contrast, 20 percent of penstemons tend to be red and attract hummingbirds. Because hummingbirds only feed on penstemon nectar and not the pollen, they more efficiently pollinate. The bees actually gather pollen to eat it and feed it to their young and thus reduce the amount of pollen being used to pollinate other penstemon plants. Penstemons in the Gunnison Basin, like those throughout North America, produce massive nectar and pollen sources and attract a large number and exceptional diversity of insects. The relatively early blooming time by penstemons helps keep insects fed before the peak flower bloom by other wildflowers later in summer. These perennial plants have aggressive roots and rhizomes that sprout into new plants, but they also reproduce through seeds. Interestingly, penstemon seed germination is stimulated after the seeds are exposed to smoke from wildfires.

(Sources: Xerces.org, Kimball and Wilson Bull of Am Penstemon Society, Salas-Arcos et al. PeerJ 2017, Americansouthwest.net, swcoloradowildflowers.com, nrcs.usda.gov, RMRS fs.usda.gov, Audubon Rockies)

Arrowleaf Balsamroot

Latin name: Balsamorhiza sagittata

Plant Family: Asteraceae, Sunflower Family

One of the most conspicuously lovely early season wildflowers is arrowleaf balsamroot. It grows at lower elevations, in sagebrush and mountain shrub ecosystems and in mountain meadows of the Rocky Mountains. As with many other sunflowers, arrowleaf balsamroot has showy yellow flowers and the actual flower consists of numerous smaller flowers (florets) including the petal-looking ray flowers and the central disk flowers. These tall wildflowers have arrow-shaped leaves up to 18 inches in length covered with hairy fuzz that prevents water loss form the leaves and helps the plant tolerate drought. An even more potent drought adaptation is the enormous root that extends three feet laterally and the tap root grows nine feet long. The outside of the root is often woody, but the center is filled with a resin (balsam). In addition to drought tolerance, the root also facilitates tolerance to disturbance such as wildfire. The plant’s root system sprouts quickly after fires. The large seeds of arrowleaf balsamroot lack dispersal structures to carry them on the wind, and therefore they drop to the soil at the base of the plant where hungry insects, mammals and birds devour them. Deer mice have a particular fondness for these seeds and unremittingly consume them leaving a depauperate seed bank. Overall, the plant has limited reproductive output but balances this by being long-lived, up to 40 years, and over that time span produces many offspring. In addition to its seeds feeding numerous species, mule deer and other wildlife relish the leaves and flowers. The flowers also attract numerous pollinators, especially native bees. In efforts to reestablish degraded habitats, arrowleaf balsamroot makes a good restoration species because it is long-lived, tolerant of drought and disturbance, provides high quality forage for wildlife and livestock, and attracts a diversity of pollinators. Some Native Americans employed antlers to dig up balsamroot for its many medicinal and edible properties. The root was burned and the incense was breathed by the runners who chased the bison over cliffs to their demise.

(Sources: Western Forbs: Biology, Ecology and Use in Restoration, https://greatbasinfirescience.org/westernforbs-restoration/ — Gucker and Shaw 2018, usda.fs.gov/wildflowers)

Scarlet Gilia

Latin name: Ipomopsis aggregata

Other names: Skyrocket, Scarlet Trumpet

Plant Family: Polemoniaceae, Phlox Family

The scarlet, trumpet-shaped flower of the scarlet gilia is very recognizable in sunny and open habitats across western North America. In the Rocky Mountains it occupies sites up to nearly 11,000 feet above sea level but also grows in lower elevation shrubland ecosystems. This species tolerates drought well and prefers drier, often rocky and disturbed soils. This sun-loving species does not tolerate shade and will not grow under dense forest canopies. In addition to the distinct flowers, the leaves have a dense covering of white hairs, giving it a lighter complexion. This species grows a basal rosette of leaves and remains in this condition for one to several years before an erect stalk shoots upward and produces flowers and seeds. After flowering the plant dies. While many individuals are biennial (live for two years), the plant is often considered a short-lived perennial with the average life span of less than five years and no plants over ten years old. Scarlet gilia attracts hummingbirds including the broad-tailed and rufous hummingbirds of the Gunnison Valley. The long, thin bills of these birds match the long-necked flower structure. Birds, with their excellent vision, can’t resist the red flower beacons.

(Sources: USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Plants For A Future pfaf.org, The Jepson Herbarium ucjeps.berkeley.edu)

Ponderosa Pine

Latin name: Pinus ponderosa

Plant Family: Pinaceae, Pine Family

Of all the conifers in the Rocky Mountains, ponderosa pines have the largest trunks (up to eight feet in diameter) and reach heights exceeding 200 feet. Some of these gigantic monarchs have stood steady for over five centuries in one spot. The classic ponderosa pine forest contains only a dozen trees per acre. This low tree density, combined with their open treetops, creates a park-like savanna. Tree huggers can attest to the delicious aromatic scent (often described as vanilla or butterscotch) of the tree’s thick orange bark. This plated bark protects the adult trees from ground fires that burn and kill the seedlings and saplings as well as shrubs and maintain a grassy forest floor under the open canopy. This open forest consisting of massive sun-loving pines may trigger a deep evolutionary memory of the origins of humans in the African savannas (a similar park-like setting) thus luring recreationists to the ponderosa pine forests. Like all pines, the leaves take the form of needles that congregate in bundles on branches. For ponderosa pine, the bundles consist of three needles that exceed five inches in length. Each of the large prickly cones harbor approximately 30-70 small seeds (12,000 seeds per pound) that take two years to develop. These seeds mature by August of their second year, and most fall within 100 feet of the tree by November. A single tree begins cone production in its seventh year and continues to produce seeds for 350 years. The seeds come in batches, and every 2-8 years, ponderosas generate seed bonanzas. Once they drop from cones, over 300,000 seeds per acre may accumulate on the forest floor. A fraction of these germinate. Life is tough for the seedlings as they battle drought, cold nighttime temperatures, hot daytime temperatures, frost heaving, fire and competition with other vegetation. Their urgent directive is to grow a deep tap root. The roots of successful individuals reach 20 inches in two months. Ponderosa pine seeds feed numerous insects, birds and rodents, including the Abert’s squirrel, which gnaws the cone-bearing branches off the tree from its lofty position in the treetops, and then descends to the forest floor where it gathers the seeds. The native pine beetle (dendroctonus) enters through the formidable bark barrier and gnaws its way through the tree, spreading a blue-stained fungus that resides in its saliva. The fungus eventually kills the tree by starvation, cutting off passage along the food delivery network. When the forest suffers from stress induced by drought or overcrowding, pine beetle epidemics, with no regard for the library of history contained in the ancient trees, can swiftly kill an entire stand.

(Sources: University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources ucanr.edu, Southern Research Station srs.fs.usda.gov)

Silvery Lupine

Latin name: Lupinus argenteus

Plant Family: Fabaceae, Pea Family or The Legumes

Growing in mountain meadows and sagebrush shrublands, these blueish-purple wildflowers delightfully color the landscape. Silvery lupine grows from the foothills to the alpine and blooms from May to September, earliest at lower and latest at higher elevations. The unique palmate leaves give the plant a distinctive appearance. As part of the legume family of plants that include peas, lupines also produce seeds in pods. The hairy pods and leaves give the plant its silvery appearance. Lupine invades disturbed sites and does well in harsh conditions. This partly results from its mutualistic relationship with rhizobium bacteria that live within houses (nodules) in the lupine’s root system. These bacteria have a special role of converting nitrogen to a form that the plant can eventually uptake and use. Only nitrogen-fixing bacteria and a few other species have the superpower of taking non-living nitrogen (which is the key ingredient of proteins and DNA) out of the atmosphere and soil. Lupines house these crucially important bacteria, which make life possible for all plants, fungi and animals. Humans could not exist on Earth without this ecological process, and the heroes are the humble microscopic organisms living inside lupines out of sight and under the soil. In addition to its ecological role in nitrogen fixation, the plant attracts numerous pollinators including hummingbirds, bees and butterflies. The term lupine means “wolf” in Latin, but it isn’t clear why the plant was named after wolves. It can kill sheep and other livestock due to toxins in the seeds and shoots. Lupine is not edible for humans, either.

(Sources: Crumbaker 2022 cnhp.colostate.edu, plants.usda.gov, Oregon State Extension)

Lupine.

Colorado Columbine

Latin name: Aquilegia caerulea

Other names: Colorado Blue Columbine, Granny’s Bonnet

Plant Family: Ranunculaceae, Buttercup Family

The iconic Colorado columbine blooms in the Rocky Mountains from spring through late summer, from the foothills to the alpine. The bicolored flower has five distinctive blue petals, each with a nectar spur and five white sepals. The nectar spurs guard the nectar and only certain long-tongued pollinators access these nectar reserves. Evidence suggests that in some populations, nectar spurs are elongating over time and becoming more custom-built for hawk moths and hummingbirds. Some columbines lack spurs and are more readily pollinated by bees. The droopy or pendulous flowers of Colorado columbines sit on a flexible base (pedicel), as do many hummingbird-pollinated flowers. However, hummingbirds do not prefer this arrangement. When hummingbirds approach a Columbine flower from underneath, they insert their bills into the flower and nectar spurs and then fly upward so they can drink at their preferred horizontal orientation which allows more efficient nectar consumption. The Colorado columbine was designated Colorado’s state flower in 1899. The genus name has its origin in the Latin word for eagle (aquila), the species name refers to the color blue (caerulea), and its common name has its Latin roots in the word “columb” which refers to doves. The “blue eagle” refers to the shape of the nectar spurs on the petals that resemble eagle talons, and the same “talons” resemble a flock of doves.

(Sources: Utah State University extension.usu.edu, Popovich 2022 fs.usda.gov/wildflowers, LoPresti et al. 2020 Annals of Botany)

Colorado columbine. Photo by Pat Magee.

Gunnison’s Mariposa Lily

Latin name: Calochortus gunnisonii

Plant Family: Liliaceae, Lily Family

The exquisite mariposa lily is unmatched in its floral grace. The delicate sun loving plant contrasts with its exuberant flower that blooms on dry sites from the foothills to the subalpine. Three large white petals interior to three slim greenish sepals are painted with a slender purple band that encircles the flower atop a ring of elegant yellow hairs. The genus Calchortus contains the Latin root “kalos” meaning beautiful and “chortos” meaning grass – referring to the slender leaves. Mariposa is a French term for butterfly. The perennial Mariposa Lily grows from a corm (or bulb), a regenerative underground stem. The entire plant is edible and the lily corm contributed to saving the Mormons in 1848 when crickets inundated their crops and besides benefitting from the serendipitous arrival of hungry gulls that gobbled the crickets, they turned to wild edibles including the Sego Lily a close relative to Mariposa Lily. The first Mariposa Lily was discovered in Colorado in 1853 by Frederick Creutzfeldt the botanist on the ill-fated Gunnison Expedition. Shortly after discovering and naming the lily for his boss (gunnisonii) both Captain Gunnison and Creutzfeldt and several others in the expedition met their demise at the hands of Ute warriors who retaliated murder of one of their people by immigrant whites.

(Sources: North Carolina Extension Gardener plants.ces.ncsu.edu, southwestdesertflora.com, americansouthwest.net, Denver Botanical Gardens botanicalgrardens.org)

Red-stem Cinquefoil

Latin name: Potentilla rubricaulis

Plant Family: Rosaceae, Rose Family

This perennial high-elevation forb grows in gravelly soils and scree from 8,000-14,000 feet. The bright yellow flowers bring color to rocky, barren substrates in the land above the trees (alpine ecosystem) from Alaska to Greenland and south to the southern Rocky Mountains. The yellow petals have a hint of orange at the base. The name cinquefoil means “five leaves,” referring to the hand-like compound leaves with five fingers, leaflets or lobes. Some plants have pinnate leaves that have tiny leaflets and look like a ladder. The plant has ground-level and below-ground stems that sprout and allow the plant to spread horizontally. Bombus bumblebees are the chief pollinators. The scientific name Potentilla comes from “potens,” meaning powerful. This derivation is associated with the plant’s medicinal uses that may include anti-aging properties in the leaves.

(Sources: Aiken et al. 2022 nature.ca/aaflora/data/www/roporu, Lee et al. 2022 MDPI, Flora of North America eFloras.org, Americansouthwest.net, swcoloradowildflowers.com)

Purple Aster

Latin name: Symphyotrichum spp.

Plant Family: Asteraceae, Sunflower or Aster Family

The genus Symphyotrichum only represents some of the Rocky Mountain and western asters. Asters are a diverse group of plants and several species occur in the Gunnison Basin. An aster differs from a daisy based on the structure of the bracts below the flowers (overlapping like shingles in asters). Asters have two unique flower types. The structures that look like purple petals are actually ray flowers (either infertile or female-only flowers), whereas the center of the flower (the gold) is comprised of 30-300 bisexual ray flowers. These compound flowers bloom late in the growing season and provide an important nectar source for late summer pollinating insects, including the migratory monarch butterfly. Asters have underground stems called rhizomes that grow up from the soil and produce new plants. Rhizomes allow aggressive spreading in this perennial species.

(Sources: extension.usu.edu, piedmontmastergradeners.org)

Paintbrush

Latin name: Castilleja

Plant Family: Orobanchaceae, Broomrape Family

Paintbrush belongs to the hemi-parasitic Broomrape family, with over 200 species of Castilleja in western North America. These plants both photosynthesize and send roots like structures called haustoria through the soil into the roots of a neighboring plant. Paintbrush sucks carbohydrates and other nutrients from the host plant. When the host is a lupine or other member of the pea family, paintbrush attracts more pollinators and produces more seeds than if paintbrush parasitizes grass. In addition to taking nutrients from hosts, paintbrush also robs host plants of chemicals that can be stored in its own tissues and used as chemical defense against herbivores. This biennial species forms rosettes of leaves during its first year. Then it forms a flower stalk with bright red or reddish-orange bracts that attract pollinators such as bees and hummingbirds. The flower sits above and between the red bracts and seeds are contained in capsules, sometimes over 300 seeds per capsule. This iconic western wildflower ranges from Alaska to the Andes Mountains in South America. In addition to parasitizing other plants and sequestering chemicals, Castilleja also sucks up selenium from the soil, sometimes to toxic levels. Nevertheless, paintbrush flowers are edible but have been used both as a love potion and poison by Native Americans.

(Sources: wildflowers.or, fs.usda.gov, Denver Botanic Gardens botanicgardens.org, Power 2018 ColoradoMountainGardener.blogspot.com)

Gunnison’s Milkvetch and Skiff Milkvetch

Latin names: Astragalus anisus and Astragalus mycrocymbus

Plant Family: Fabaceae or Legume/Pea Family

Not one but two unique endemic plants from the Pea Family, called Milkvetches, live in the Gunnison Basin. Gunnison’s Milkvetch and Skiff Milkvetch exist nowhere else in the world except within a 35-mile radius of Gunnison. This extremely small distribution makes both species vulnerable to extinction (the Skiff Milkvetch was considered for listing under the Endangered Species Act). With most populations on the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) property, the agency designated an Area of Critical Environmental Concern in the South Beaver Creek to help protect these sensitive species. Both species come from the genus Astragalus, the largest genus of plants in the world with over 3,000 species. The term means ankle bone or neck vertebrae and refers to either the seed or flower shape in milkvetches. The species name for Skiff Milkvetch is “mycrocymbus,” which means little boat (skiff) and refers to the shape of the seed pod that forms after leafcutter bees pollinate the flowers. The Astragalus genus split from ancestral pea species 130,000 years ago and evolved into unique endemic species during that time. The compound leaves of these species have multiple leaflets, and resemble a ladder. The hairy covering on the leaves reduces water loss and the leaves appear light green. The diminutive flowers, whitish-purple in Skiff and pinkish-purple in Gunnison’s Milkvetch, mostly bloom from May to June in the sagebrush sea and add a subtle seasoning to the summer wildflower spectacle. Construction of new roads and trails, and off-road and off-trail activity by motorized and mechanized recreationists represent the largest threats to these vulnerable plants. Rabbit herbivory and climate change are also threats.

(Sources: Decker and Anderson CNHP 2004, NatureSErve, Taylor 2022)

Gunnison’s milkvetch. Photo by Bronwyn Taylor.

Big Sagebrush

Latin name: Artemisia tridentata

Plant Family: Asteraceae or Sunflower Family

Oh what would the Gunnison Basin be like, without big sagebrush? This iconic shrub gives an unmistakable identity to the Gunnison Basin, often called the sagebrush sea. The plant has adapted to the harsh conditions of the Gunnison Valley—intense winter cold and intense summer drought. Sagebrush taps into soil moisture with long roots, sometimes exceeding ten feet. This adaptation allows these hardy shrubs to drink from snowmelt deep in the soil. They are drinking from a different time and place. Sagebrush also have a horizontal root system that collects the surface water from summer rain. Drinking allows sagebrush to live in the intensely arid Gunnison Basin, but the species also has key water conservation strategies. As with many plants living in desert ecosystems, sagebrush leaves have a hairy covering. These low-growing shrubs also stay closer to the ground to reduce water loss from the wind. Sagebrush remains green year around. However, a caveat to this pattern is that some of the leaves are deciduous, and after growing in the spring, they fall off the plant in early summer as drought intensifies. The leaf surface area both enhances the plant’s ability to photosynthesize and increases water loss. A compromise allows a portion of sagebrush leaves to drop from the plant in June when water loss becomes a threat to the plant’s survival. Sagebrush flowers develop slowly over summer. Wind carries the pollen throughout the sagebrush sea, allowing pollination to occur in late summer. Then the seeds develop and ripen by mid-fall. Each plant harbors thousands of tiny seeds which fall to the ground and may be blown by wind. The term “tridentata” means three-toothed referring to big sagebrush leaf shape. These leaves are loaded with chemicals that not only give sagebrush is distinct and alluring odor but also act as inhibitors to herbivores. While the leaves may be bitter, they have high protein content. Mule deer and elk consume them in winter as a high-quality food source. The Gunnison sage-grouse also eats the leaves, and in winter, sagebrush leaves account for well-over 90% of their diet. Sagebrush and sage-grouse have evolved together for hundreds of thousands of years, and sage-grouse so rely in sagebrush that they can’t live anywhere else. They are called sagebrush obligates. In addition to sage-grouse, many other wildlife depend on sagebrush and thrive in the sagebrush sea, including migratory songbirds (Brewer’s sparrow, sagebrush sparrow, sage thrasher). Mammals that depend on sagebrush are mule deer, elk and pronghorn. Sagebrush is also important to carnivores, from wolves and grizzly bears to short-tailed weasels and the butcher bird!

(Sources: Shultz 2012 Sagebrush Pocket Guide, PRBO)

Mountain biking through sagebrush at Hartman Rocks.

Where to find these plants

Take a mountain bike ride at Hartman Rocks or a hike in the West Elk Wilderness to observe these plants in the wild. You’ll also see them on the shores of Blue Mesa Reservoir and in Curecanti Recreation Area. The wildflowers in particular bloom at Hartman Rocks and Signal Peak in late spring and early summer. The range of many of these plants extends into the Gunnison National Forest towards Crested Butte, too. Although these plants are common around Gunnison, they also abound in much of the Rocky Mountain region. Similar ecosystems exist around other Colorado cities like Durango, Salida, Steamboat Springs, Pagosa Springs and Buena Vista.